Houston defective products law firm, Patrick Daniel Law, has some of the most knowledgeable and experienced product liability attorneys and defective product lawyers in Texas. Our Houston products liability attorneys protect consumers against defective products and know the kinds of tricks product manufacturers and product designers try to play on consumers. Our defective product attorneys also know all the games Houston insurance companies try to play and we’ll help you to avoid some of these traps.

If you were injured by a defective product in Houston, Harris County, or nationally, our defective product lawyers want to hold all people in the supply chain liable. Our product injury attorneys want to hold all those who allowed the product to come to market liable. Businesses should not release a faulty product or bad product design, especially if they know the product may cause injury. If you’re looking for a Houston product liability law firm, Patrick Daniel Law is here to defend you and help you to recover your losses after your injury.

Our Houston defective product attorneys are experienced, knowledgable and will work 24/7 to ensure that justice is served in your product liability case. If you would like to speak with one of our products liability attorneys at our Houston law office for a free consultation, call (713) 999-6666 or contact us online.

If you were injured by a defective product in Houston, or anywhere else in the nation, and would like a free consultation with our Houston product liability law firm, contact Patrick Daniel Law by calling (713) 999-6666 or contact us online.

Consumer products are manufactured to be consumed. Whether they work as advertised, endure long enough to justify their cost, or are safe to use, are all too often secondary concerns of the manufacturer. Efforts to improve products are often the result of competition, not due to heartfelt concern for consumers. This is why a lot of defective products get pushed out into the market.

So, when things go wrong; when faulty steering causes an accident; when a defective or dangerous toy mars a child’s face; when the clothes dryer overheats and starts a fire, someone should be held accountable and be made to compensate the injured party. If you are that injured party, contact the defective product lawyers in Houston, Texas – Patrick Daniel Law. Our Houston product liability law firm will defend you, fight for you, and do our best to help you win and recover after a defective product injury.

Product liability cases are time-consuming, frustrating and rife with legal pitfalls, but the Houston defective products legal team at Patrick Daniel Law has the experience, patience and the passion to provide clients the settlements they deserve, no matter what it takes.

To be product liability lawyer in Houston, San Antonio, Dallas or anywhere in Texas or the U.S., you must fully understand the legal process regarding claims. You can’t allow yourself to be broadsided by the various stalls and dodging maneuvers used by manufacturers and their representatives. Plus, you must also know the product and the system by which it is manufactured.

Patrick Daniel Law is a products liability law firm in Houston and already knows products liability law as well as the many state-by-state variations. The other part – knowing the product and the manufacturing process thoroughly – comes with diligent research. By the time your case goes to trial, our Houston products liability lawyers will be consummate experts in the product, and in how it is supposed to work and why it didn’t in your situation.

They are more than just product liability attorneys. They are dedicated consumer safety advocates, which is why they are eager to litigate product liability claims for their clients. If you need a products liability legal team or would just like to consult with a Houston defective product attorney, click here to receive a free case evaluation.

Products liability law in Houston and in the U.S. has its roots in 19th Century English law. The laws as many Houston product liability law firm’s know them today began with the iconic Winterbottom v. Wright case of 1842.

Mr. Winterbottom was a postal carrier who was severely injured when the mail coach he was driving collapsed due to shoddy workmanship. The maker of the coach, Mr. Wright, did not sell the coach directly to Mr. Winterbottom, but rather to the local postmaster, with whom he had a contract.

There was no contract between Mr. Winterbottom and Mr. Wright, and for that reason, the court dismissed the lawsuit. At that time, there was no such thing as product liability, so the only thing the court could rule on was whether there had been a breach of contract. So, since there was no contract, there could be no breach of contract.

The court argued that awarding Mr. Winterbottom compensation would open the door to many more lawsuits on the same basis.

“If we were to hold that (Winterbottom) could sue in such a case, there is no point at which such actions could stop. The only safe rule is to confine the right to recover to those who enter in to the contract,” wrote the British Lord who ruled on the case.

But that setback to modern product liability was eventually overcome.

You have a right to expect that any product you buy, regardless of the retail venue, will work like it’s supposed to and it will be safe for you to use. It makes no difference if you signed a contract, agreed to any terms or made any promises regarding its use – you are protected.

Formerly, it was the manufacturers of products who were protected – by a provision known as privity. Under privity, only those parties included in a contract could sue one another, and only for breach of contract issues, such as the seller failing to inform the buyer of any inherent dangers in the product. Otherwise, it was assumed that the buyer already knew of those things.

But in MacPherson v. Buick Motor Co. (1916), a New York court of appeals ruled that the plaintiff could seek compensation from Buick, even though his car (which had a defective wheel) had been bought from a dealer and not directly from the manufacturer. Donald C. MacPherson had signed no contract with Buick and made no admission that he was aware of any inherent danger with the car or the wheel that failed.

In joining two other justices in a ruling for the plaintiff, Justice Benjamin Cardozo wrote, “Irrespective of contract, the manufacturer of this thing of danger is under a duty to make it carefully. . . if he is negligent, where a danger is to be foreseen, a liability will follow.”

After MacPherson v. Buick Motor Company, a consumer no longer had to have privity (a contract) to file a product liability suit if he was the original purchaser of the product and its sole user. However, subsequent owners of the item in question had no established legal recourse if they suffered injury, even if a defect could be traced back to the manufacturer.

This policy – that subsequent owners or alternate users of a product could not sue for damages due to defects – was never expressed in written law but was practiced universally for nearly half a century. Bills of sale often included disclaimers to that end and added stipulations that would seem to limit sellers’ liability if certain conditions existed, but challenges to the practice gained attention over time.

The challenge that broke through the invisible barrier came when the New Jersey Supreme Court ruled for the plaintiff in Henningsen v. Bloomfield Motors Inc. in 1960. There, Claus H. Henningsen bought a car for his wife, but he was listed as the buyer on the bill of sale. In addition, he signed a disclaimer form that listed the provisions and limitations of a warranty on the car.

When the steering failed and caused Mrs. Henningsen to wreck the car, the seller refused to repair the car (actually replace it, as it was deemed a total loss), stating that the warranty that Mr. Henningsen had signed provided only for the replacement of defective parts and nothing else.

Mr. Henningsen sued. The defendants claimed that the disclaimer that Mr. Henningsen signed superseded all other warranties, regardless of whether they were expressed in writing or implied. The lower court ruled in Mr. Henningsen’s favor, but it was appealed, and the case eventually made it as far as the New Jersey Supreme Court.

The New Jersey Supreme Court established a precedent that is now a vital part of product liability cases – the concept of implied warranty. Simply put, implied warranty states that a product is assumed to be suitable for use by anyone who uses it, whether he or she was the original buyer and in spite of any disclaimers or limited warranties he or she might have signed.

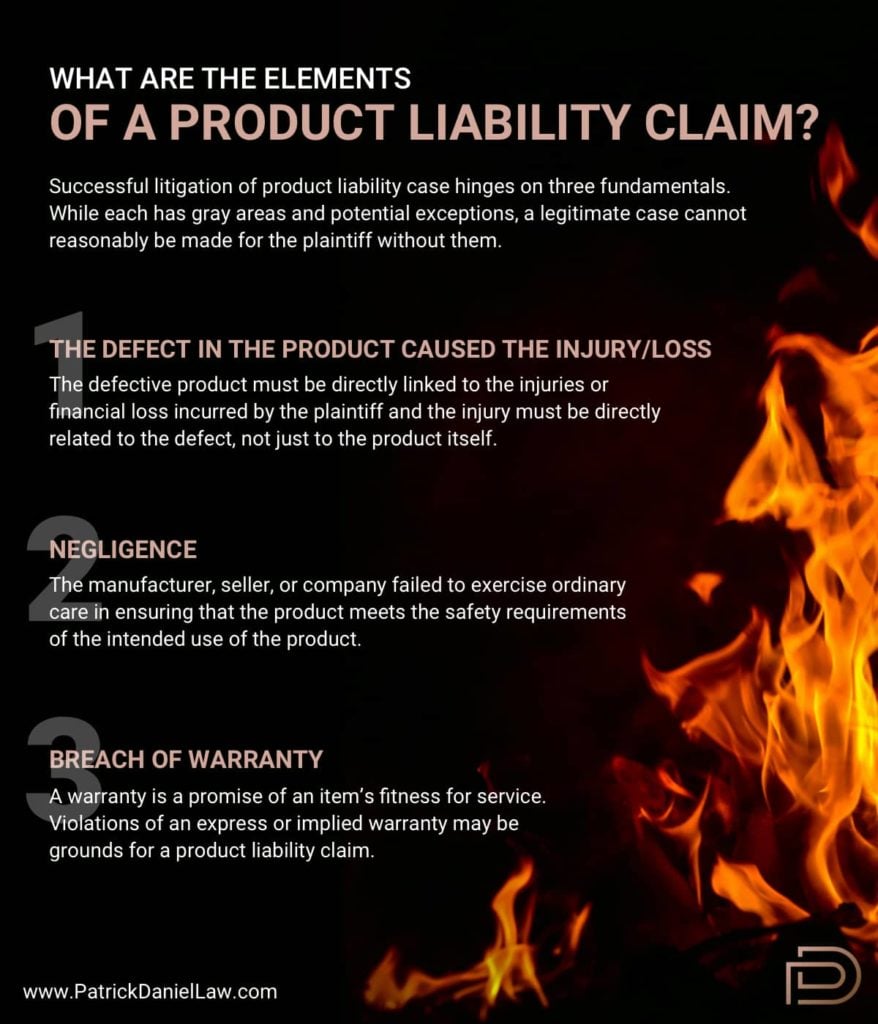

Successful litigation of product liability case hinges on three fundamentals. While each has gray areas and potential exceptions, a legitimate case cannot reasonably be made for the plaintiff without them. Often a defense team will let one or even two of these elements go by with mere token resistance, but dig in on the element they feel most likely to prevail on.

The defective product must be directly linked to the injuries or financial loss incurred by the plaintiff and the injury must be directly related to the defect, not just to the product itself.

This invokes the “if not for” rule. Simply stated, it means “if not for the bad welds, the beam would not have collapsed under load,” or “if not for the warped rotor, the brakes would have stopped the truck in time.”

Unrelated defects or failures are not typically considered in product liability cases, unless they show a pattern of negligence that may have contributed to the specific failure that caused the injury.

Negligence isn’t as dark and sinister as many make it out to be. It simply means that the manufacturer, seller, or company failed to exercise ordinary care in ensuring that the product meets the safety requirements of the intended use of the product. In some cases, there are state-mandated standards that must be met; in others, “ordinary care,” must be exercised.

So what is “ordinary care?” It’s a concept that indeed has some gray areas, but essentially it implies that a reasonable person would do this, or check that or report anything that seemed suspicious in order to ensure that the product would perform as expected and more importantly, present little or no danger to the user.

Ignorance of the danger posed by a product is no excuse, a risky product is a risky product. Manufacturers and sellers should by default be the ultimate experts on their own products. They should know what they’re capable of when they’re used correctly and what they’re capable of when used incorrectly.

The exercise of ordinary care is considered a duty that is owed to the consumer. It’s not a bonus or a perk. It’s a duty. In some states, the term “breach of duty” may become part of the terminology of the case. The duty owed to consumers must also include vital information about the product, advice on safe handling and warnings on the dangers of misuse, as well as the inherent dangers of the product even when used in accordance with the recommendations.

Improper use of a product by the consumer may weaken his case, but he may still have a case. Some states have policies regarding contributory negligence or comparative fault. In order to figure out the difference you’ll want an expert products liability attorney to determine this for you. Houston products liability law firm, Patrick Daniel Law, and their defective product attorneys can help you figure out important differences like these.

A warranty is a promise. The manufacturer promises that if A happens, it will respond with B. This can apply to the working condition of the item, its appearance, durability or its safety. Example: “If the built-in battery fails, send your tablet in for a replacement, or if the blade goes dull, we will replace the blade free of charge.”

But beyond an after-the-fact response, a warranty is a promise of an item’s fitness for service, and it’s required. The law governing the sale and shipment of consumer goods is under Article 2 of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC), which applies in every state in the union.

1. Express Warranty – Affirms certain aspects about the product and promises in writing that the product satisfies the statements in the description. An express warranty can be a bargaining tool in sales negotiations, assuring the buyer that the product is what it says it is in all aspects that are expressed.

The express warranty sets forth conditions that enable, modify or render invalid the warranty’s provisions. However, ever since Henningsen v. Bloomfield Motors Inc., the express warranty cannot supersede the implied warranty.

2. Implied Warranty – Affirms that the product can reasonably be expected to perform as intended and will be safe to operate if used properly. It says that if you buy a blender, you can assume it will blend foods and make smoothies and milkshakes. Putting things down on paper as a promise is not necessary.

There are two sub-categories of implied warranties: the Implied Warranty of Merchantability means that the lawn mower you bought from Home Depot will always be recognized as a lawn mower in all potential resales and will operate as expected as a lawn mower for any future owners.

The other subcategory is the Implied Warranty of Fitness for a Particular Purpose. The product is to be used for a particular purpose, and the seller affirms that the product is suitable and safe for that particular purpose.

The only way an implied warranty can be nullified is if the buyer clearly and unambiguously disclaims it in writing as part of the bill of sale. If a buyer intends to dismantle the lawn mower and use the engine in a go-kart, and he disclaims the implied warranty in writing, then he vacates his right to sue the maker or the seller for breach of warranty if something goes wrong.

When you contact Patrick Daniel Law to file a product liability claim, you should be able to provide clear information about your situation. They can guide you through the process and help you organize your thoughts and determine what the best course of action should be.

Sometimes, all it takes is the hiring of a products liability attorney to get results. Liability insurance providers and their attorneys might decide that compensating you a fair amount for your loss is a better option for them than litigating the matter in court.

If you would like a free consultation with our Houston product liability law firm, call (713) 999-6666 to speak to a defective product attorney in Houston.

During production, someone or some machine made a mistake. It could be due to an oversight, a shortcut, distraction, lack of communication between employees or departments and simple ignorance of the proper techniques.

As far as your lawsuit is concerned, it doesn’t matter if the mistake was easily avoidable or not. Good people make mistakes, but when people are injured by them or suffer loss, the person (or company) who made the mistake is liable. That’s how the law works.

Product designers are responsible for designing products that work efficiently, provide comfort and safety to the user and are aesthetically pleasing. Sometimes, designers get carried away with the aesthetically pleasing part and overlook important factors in the comfort and safety part.

Occasionally, design defects do their damage slowly. You might have a product liability case even without a sudden, loud, catastrophic accident that brought co-workers rushing to your aid. The damage can be subtle, as with a poorly designed handle that led to carpal tunnel syndrome; or perhaps a product with poor weight distribution causes back trouble. Granted, proving that the design was inherently faulty is often a challenge, but the law is clear that manufacturers of consumer goods must keep user safety at the forefront of their designs.

Missing or Insufficient Warning. Manufacturers are required to warn buyers of all potential dangers with their products and with the way they are used or misused. Even ridiculous examples of misuse must be addressed, such as not moving a ladder if someone is on it. Proper work technique and product instructions must be clearly communicated, without regard to “common sense.”

Courtroom debate often centers on what the user “should have known” or how the user “should have used common sense.” But product liability law typically puts the burden of “should have” on the manufacturer. The manufacturer should have warned that using the product a certain way could result in injury. There are limits, of course, and the notion of common sense does win out when merited, but it doesn’t happen as often as you might think.

For example, in 1992, Stella Liebeck should have known that the McDonald’s coffee she purchased was hot and that if she spilled it on herself, she would suffer burns. But what she didn’t know, and, more importantly, what she wasn’t told, was that the coffee was extremely hot. Corporate rules from McDonald’s instructed franchisees to serve coffee at 180 degrees.

This was hot enough to produce third degree burns when Mrs. Liebeck spilled her entire cup in her lap. Some accounts of this story state that Mrs. Liebeck was driving when she spilled her coffee. In actuality, she was a backseat passenger and car wasn’t even moving at the time of the mishap. She sued for the cost of her medical bills and loss of income.

The jury deemed that McDonalds should not have served coffee at that high of a temperature, and furthermore, should have warned that the coffee could cause severe injuries in seconds if spilled on a person’s skin. The award amount of nearly $3 million created headlines, but the award did not reflect Mrs. Liebeck’s demands – she was willing to settle for $20,000. The jury set forth that amount because a pattern of similar incidents involving hundreds of other customers had not been addressed by McDonalds.

Very often, when a criminal case ends up with a not guilty verdict, it’s not because the accused is truly innocent, but because his accusers failed to prove his guilt.

While the burden of proof in a product liability case is less cumbersome than that of a criminal case, it’s still a stern challenge. It’s for the good of all, as it helps rid the docket of frivolous lawsuits.

Therefore, your product liability lawyer has his or her work cut out for them. You can help by providing acceptable evidence that supports your claim that you were injured by a defective product. These are areas where proof is not only essential but expected. Otherwise your case might not get past first hearing.

Proof that you were injured and / or suffered financial loss. This sounds simple enough, but without medical intervention – and proof thereof – your case is compromised from the start. If you missed paychecks not covered by workman’s comp or if you lost out on business opportunities, you should provide clear documentation.

The “if not for” rule applies here too. “If not for my shoulder separation, I would have made $16,000 between March and July.”

Proof that the product was defective in design or manufacture, and / or lacked sufficient warning labels. This is where having an experienced products liability lawyer becomes a crucial part of the equation. Take the time to write down an account of your experience with the product. Note what you expected to happen versus what actually happened. Provide photographs if possible. Your defective product attorney can take it from there.

Also, make it clear that you followed the instructions, took all appropriate precautions and paid attention to what you were doing. If you contributed in any way to the mishap, be honest and admit it. That hurts your case, yes, but it doesn’t let the manufacturer off the hook. There remains some expectation that a product will be reasonably safe, even when misused.

Proof that the Product Defect Caused your Injury. There must be a direct correlation between your injury and the part of the product that failed or was found defective. If the opposition is going to let this go to court, you can be assured they will make your side prove this point above all others.

Simply being injured – whether immediately in a mishap or over time – by a defective product is not enough to sway most judges and juries. You must link the manner in which the product failed to the manner in which you were injured. If a spinning fan blade flies off its shaft and strikes you, that’s a direct correlation. If you duck, and the fan blade misses you, but you slip and fall on hard concrete, the defense will likely assert it was the concrete that caused your injuries.

The “if not for” illustration passes muster for acceptable and convincing argument. “If not for that defective fan, and if not for that fly-away fan blade, I would not have been rushed to the emergency room with severe cuts on my head.” This is what you need to be able to say, whether in a deposition or in open court, to make a solid point to support your case.

One thing both sides of a product liability suit can agree on is that each would rather settle out of court. That’s nice but hold the phone a minute.

The dream ending for both plaintiff and defendant is to settle the dispute out of court, quietly, sedately, out of public view. The plaintiff is spared an emotional reliving of perhaps the worst moments of his life and is spared a daunting public grilling where he starts to doubt his own words. On the other side of the table, the defendant, often a company that depends on public trust for its success, is spared a black mark on its image.

Early on, the motivation to settle out of court clearly rests with the defense. Often, they are willing to settle on a case they could possibly win just to keep the matter out of public view. But they want to do it on their terms, with the lowest possible dollar amount and the least amount of public noise possible.

Representatives of the company, or of their liability insurance provider, will often glad-hand the victim with an offer that’s heavy on promise but light on deliverance. The earlier in the process the offer comes, the more you can know that they are low-balling you. You should let them know you’ve contacted a battle-tested product liability attorney, like Patrick Daniel Law, and see how they change their happy message.

This doesn’t mean they’ll snatch the papers off the table and storm out the door, screaming “We’ll see you in court!” If anything, it ramps up the possibility that they will settle out of court, and increases the chances that they will come back to the table with a settlement that more closely resembles what you could live with.

The defense team is more likely to settle out of court under these conditions:

You’ll notice that “they want to do the right thing” was not listed. While it’s not fair to the number of companies who do have hearts to suggest that they all are concerned only about the money, the “profit first and always” attitude is a reality in our legal system that can’t be overstated.

Litigating your own product liability case can be a rewarding experience or a nightmare you’ll never want to go through again. Each case is different, both in the circumstances that led to the claim, and in the way the claim proceeds through the court system.

The claims process is straightforward and easy to understand. If you can provide documentation that is accurate and clearly stated, it can open doors (and checkbooks). Vast knowledge of legalese is seldom necessary.

You know what happened. It’s the old adage of “If you want it done right, do it yourself.” In your case, it’s “if you want the story told right, tell it yourself.”

The court wants your case settled quickly. Many states have compensation structures that set benchmarks for different types of lawsuits. Often, those benchmarks are more than fair to the plaintiff, and often, the defendant’s insurance company will agree to pay out of court, as long as the plaintiff has compelling documentation.

Save on legal fees. Most product liability lawyers will take on your case on a contingency basis, taking their fees out only if you win your case. If the case is simple, and is settled easily, the plaintiff might receive just as large a settlement as he would have if represented by an attorney, but he gets to keep the money that would have gone to the attorney.

Nothing gets the attention of the other side better than hiring an attorney. If you represent yourself in your claim, you lose that clear advantage, and it’s often a game- changer.

An attorney has contacts you may need. Expert witnesses often turn the tide of a court case, and a well-established product liability attorney has a Rolodex full of them. Expert witnesses can be physicians, therapists, researchers, government officials or local experts in the product that caused your injury.

Complex cases need experienced litigators. As mentioned earlier, if your product liability case is simple, you might not need an attorney. But frequently, the case gets complicated, and it’s often the other side that makes it so.

There are tricks, pitfalls and roadblocks that would befuddle an amateur litigator and put his case at risk. In fact, if you choose to represent yourself, you may be unwittingly inviting the defense to put on a legal show of force designed to intimidate you and expose your lack of expertise.

Nearly a million people a year are injured in power tool accidents, resulting in 200 fatalities. Most of those accidents can be attributed to operator error, but even those caused by the user can expose outcomes that the manufacture should reasonably be expected to have foreseen.

Power tools carry with them an inherent risk that even the most novice user can appreciate. Power tools cut, whirl, punch, crush, chop, pound, scrape and grind. Any body part that gets in the way is asking for trouble, and any user who picks up a power tool without knowing fully how to use it is asking for trouble.

Product liability cases against power tool manufacturers (and sellers and rental businesses) weigh heavily on the experience level of the user. The defense will vigorously assert that the user did not follow proper techniques for the equipment’s usage, plus point out the various warning labels and manuals designed to keep the user safe. It’s their only hope of winning the case, if it has already been established that the product directly caused the injury.

Like automobiles, power tools pose a risk, not only for the user but for those nearby. In a bizarre incident in 1986, Eugene Doran was getting a haircut when a nail from a nail gun being used next door came through the wall and struck him in the spine, paralyzing him.

The carpenter using the tool was unaware that there was no solid wall between the shop where he was working and the barber shop next door. The nail penetrated the sheetrock and struck Doran with enough force to sever his spinal cord.

Doran sued the nail gun manufacturer and the company that rented the nail gun to the worker on the grounds that they did not adequately warn the worker of the inherent danger of the nail gun. The defendants settled with Doran on the second day of the trial for a reported $15.35 million.

There are three types of product liability cases regarding medications: (1) Defective manufacturing, (2) dangerous side effects and (3) deceptive marketing.

Defective manufacturing can be the result of unsanitary facilities, improper storage, improper labeling and improper handling.

The key question is whether the manufacturer or reseller knew about dangerous side effects and whether those dangerous side effects were clearly defined in product literature.

In addition to warning of potential side effects, product literature should clearly indicate how the drug is to be used, what it treats, what it doesn’t treat and the reasonable expectations of using the drug.

Food producers / manufacturers / resellers are held to exceptionally high standards in regard to food safety. The best ones strive for zero defects, not just an acceptable number of defects. To them, zero is the only acceptable number.

But the reality is, no food producer is perfect, no shipper, no grocery store, no restaurant and no corner deli. Food poisoning, food contamination and food allergens create a frightening gauntlet of threats for consumers. The list of potential defendants in a product liability lawsuit is a long one and can include:

Food can be left out at room temperature too long, frozen, thawed and re-frozen, stored in the presence of contaminants and more. Your case can be filed on a theory of negligence – that a party anywhere within the chain of distribution knew there was a problem and did nothing to remedy it or alert the consumer to its existence. Even if a specific problem is not precisely detected, it is their responsibility to reasonably foresee problems and address them.

As you bring your product liability case forward, you will be expected to prove that you were injured (made ill) by the food because of the defect. Recurring issues, like nausea, diarrhea, insomnia and other infirmities can also be the basis of a suit, but you must be able to link the condition to the food, and the particular defect in the food.

Failure to warn of allergens, like peanuts, can also comprise a case, as does the failure to warn of hot plates, hot beverages and hot food items.

There is much, much more to product liability law than any one article can hope to cover adequately. Even the Houston product liability lawyers at Patrick Daniel Law don’t know everything about every product, but they know to find out.

Not only will they find out about the product that injured you, our Houston product liability lawyers will investigate previous cases involving people who may have had the same experience as you. It’s possible that there is an ongoing products liability case against a manufacturer that you can join as an additional plaintiff.

If you have a winnable case, they will tell you. If you don’t, they will tell you that too. The first consultation is free, and if they take your case, their fee will come out of the settlement award, not out of your pocket. Our Houston defective product lawyers are looking to fight for you though, not just settle. Settling is easy and it’s not always the best action to take in a products liability case.

It never hurts to get an experienced products liability attorney on your side early in the process. Even if your personal injury claim seems to be moving along in the right direction, products liability cases have a nasty habit of stalling at the last minute. The cooperation you received early on can suddenly turn to opposition and intimidation.

Top Truck Accident Lawyer in Pasadena

Top Truck Accident Lawyer in Pasadena Best of The Best Attorneys

Best of The Best Attorneys Best of the Best Houston Chronicle 2021

Best of the Best Houston Chronicle 2021 Best Motorcycle Accident Lawyers in Houston 2021

Best Motorcycle Accident Lawyers in Houston 2021 American Association for Justice Member

American Association for Justice Member The National Trial Lawyers 2016 – (Top 40 under 40)

The National Trial Lawyers 2016 – (Top 40 under 40) Multi-Million Dollar Advocates Forum 2016 (Top Trial Lawyer)

Multi-Million Dollar Advocates Forum 2016 (Top Trial Lawyer) Million Dollar Advocates Forum 2019 (Top Trial Lawyer)

Million Dollar Advocates Forum 2019 (Top Trial Lawyer) America’s Top 100 Attorneys 2020 (High Stake Litigators)

America’s Top 100 Attorneys 2020 (High Stake Litigators) Lawyers of Distinction 2019, 2020 (Recognizing Excellence in Personal Injury)

Lawyers of Distinction 2019, 2020 (Recognizing Excellence in Personal Injury) American Institute of Personal Injury Attorneys 2020 (Top 10 Best Attorneys – Client Satisfaction)

American Institute of Personal Injury Attorneys 2020 (Top 10 Best Attorneys – Client Satisfaction) American Institute of Legal Advocates 2020 (Membership)

American Institute of Legal Advocates 2020 (Membership) Association of American Trial Lawyers 2018 - Top 100 Award recognizing excellence in personal injury law

Association of American Trial Lawyers 2018 - Top 100 Award recognizing excellence in personal injury law American Institute of Legal Professionals 2020 (Lawyer of the Year)

American Institute of Legal Professionals 2020 (Lawyer of the Year) Lead Counsel Verified Personal Injury 2020

Lead Counsel Verified Personal Injury 2020 The Houston Business Journal 2021

The Houston Business Journal 2021